Natalia Toral

Portland Event Planner

Hello.

I may have gone a little overboard with the details on this page; but only because I wanted to turn a simple dinner into something a bit more meaningful. This gathering is a small celebration of culture, connection, and curiosity, inspired by Mexico and Día de Muertos.

You’ll find the invitation and dinner details at the end of this note. I’d love to have you there and hear your stories around the table.

DÍA DE MUERTOS?

In most Mexican households, Día de Muertos is a multi-day celebration honoring loved ones who have passed. During this time, the veil between the worlds of the living and the dead is said to grow thin, allowing spirits to return and visit their families.

The festivities traditionally begin on October 31 and continue through November 2, with November 1 (Día de los Angelitos) dedicated to the souls of children and November 2 (Día de los Muertos) honoring adults.

To welcome the spirits home, families create ofrendas—altars adorned with flowers, candles, food, photos, and cherished mementos—transforming grief into beauty, remembrance, and celebration.

THE SWIFTEST HISTORIA

Two cultures were smashed together to create the present-day Día de Muertos.

Long before Spanish colonization, the Aztec Empire held a month-long festival in honor of the dead. Communities came together to build grand altars draped in cempohualxóchitl (the Nahuatl word for marigold: sem-poh-wahl-SO-cheetl) and to pay tribute to Mictēcacihuātl (bless you: mee-teh-kah-SEE-wah-tl) the Lady of the Dead and Queen of the Underworld. She’s often depicted as a crowned skull, mouth open to swallow the stars and cast night over the earth. (The belle of the ball)

After the Spanish conquest, Catholic traditions began to merge with Indigenous beliefs. Over time, the ancient festival honoring Mictēcacihuātl fused with the Christian observance of Allhallowtide (All Saints’ Eve, All Saints’ Day, and All Souls’ Day).

Today, Día de Muertos stands as a radiant blend of both worlds, part Aztec ritual, part Catholic reflection, a celebration of ancestry, beauty, and the enduring tether between life and death.

SUGAR SKULL

In 1910, a Mexican artist created a satirical icon called La Calavera Catrina, which was printed in a Mexican newspaper depicting a “dapper skeleton” of a victorian woman. The image was meant to poke fun at those who were aspiring to be more European in their beliefs of the afterlife. Over the next 100 years, Catrina became a focal point of the Día de Muertos culture. Proposing that posthumous everyone becomes equal, money has no meaning and we are all rich (and fancy Victorian women*) in the afterlife.

Another notable work is a 50ft mural done in the late 1940’s by Diego Rivera (whose full name was Diego María de la Concepción Juan Nepomuceno Estanislao de la Rivera y Barrientos Acosta y Rodríguez) in Mexico City. The work’s name is almost as long as his! Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda Central (Dream of a Sunday Afternoon) located at the Alameda Church in city center DF.

In 1985, a devastating quake ruined the buildings around the mural, but it was meticulously moved to a museum. Just look at how beautiful it is!

What stands out to me about Halloween-(and our culture in general) is how we teach ourselves to fear things like skeletons, as if they’re something dark or dangerous. But skeletons are our structure. The framework that holds us up.

DdM offers a beautiful contrast: it approaches death with joy and reverence, celebrating it as a natural part of life. People paint their face in bright designs to honor the connection between life and death. We will too.

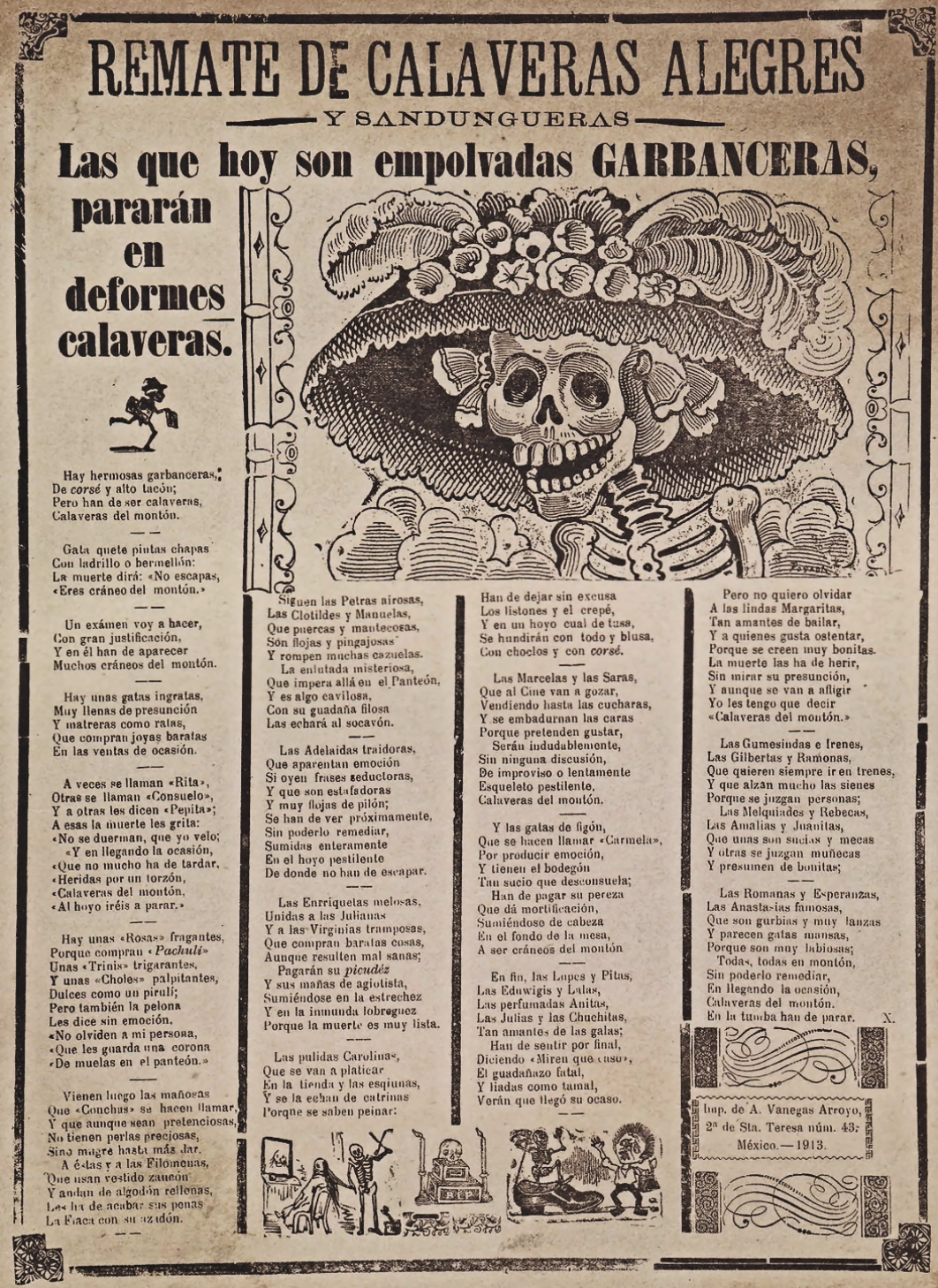

CALAVERAS LITERARIAS

Writing calaveras literarias (literally “skull literature”) rhyming poems that mock the dead or playfully satirize the living has become a cherished tradition. While the holiday honors those who have passed, it is not a time for mourning. Instead, it celebrates the lives of lost loved ones with joy and humor. A longstanding custom encourages schoolchildren to craft witty, rhythmic calaveras that bring levity to the concept of death, often targeting relatives or notable figures.

It’s a heartfelt roast: a playful tribute to those who have left us.

A FAMOUS DÍA DE MUERTOS CELEBRATION

In San Andrés Mixquic, a little town outside of Mexico City, Día de Muertos has become a main attraction to tourists. Similar to the images you’ve seen in movies, like Disney+Pixar’s Coco, the entire city comes to life with colorful banners, marigolds, altars, and skulls. Of particular interest in San Andrés Mixquic: on the nights of October 31-November 2, families gather at the central church and cemetery and build huuuuuge ofrendas on the graves. Incense and thousands of candles are lit, creating a stunning illumination (La lumbrada) in hopes their lost friends will ascend back to Earth.

MISC FACTS

Here’s some old-ass Aztec words in the English language, adopted from Nahuatl: shack, chia, avocado, guacamole, chili, cacao, chocolate, coyote, and tomato. Aztecs were healthy mofos! (Except for the making pozole out of human flesh thing…) And, the Nahuatl culture, though slowly dwindling, is one of the most researched and documented in the world.

Día de Muertos never had a parade until the James Bond movie Spectre depicted a really badass parade in Mexico City. Now, it’s a thing in most of the country.

Traditional faire of Day of the Dead include tamales, pozole, pan de muertos, beans, flan, and drinks like horchata, Pulque (like tequila), and Jamaica (hibiscus juice, which I’mma make)!

Mole is a real head scratcher but here’s a few takeaways: there are countless kinds of mole (30+?), and all usually have a long list of ingredients, many without chocolate, and they come in several colors (green, red, black), but all of them have one common denominator: chilies and spices! The reason for the variety is that the word “mole” derives from the Nahuatl word molli, which just means “sauce.” Oaxacan mole is likely the most famous and the state is nicknamed “Land of 7 Moles”. So, mole is like your grandmother’s chicken soup recipe: slight variations depending on family preference, region and economic resources.

WHY THIS IS IMPORTANT TO ME...

I was born in Mexico City, where I was first raised by my Indigenous Mexican family; speaking Spanish, eating tamales, and climbing ancient pyramids with my primos. Just as I was learning to swim without floaties and poop on my own, a devastating earthquake shook from Popocatépetl, the stratovolcano just outside of DF.

My parents were rock musicians, and their recording studio was reduced to rubble. I was put on a plane with a family friend and sent to live with my white grandparents in Long Beach, California, a separation from my Mexican family that would never quite be amended.

My Bend-born, blonde-haired, blue-eyed mom had lived in Mexico through her early 20s, recording albums and soaking up the culture. She was welcomed into the locals’ way of life with open arms and passed down so many of the traditions — how my abuela made her rice, tacos de flor de calabaza, and pozole. But at best, it’s always been a distant connection to Mexican culture… and I still want to know more.

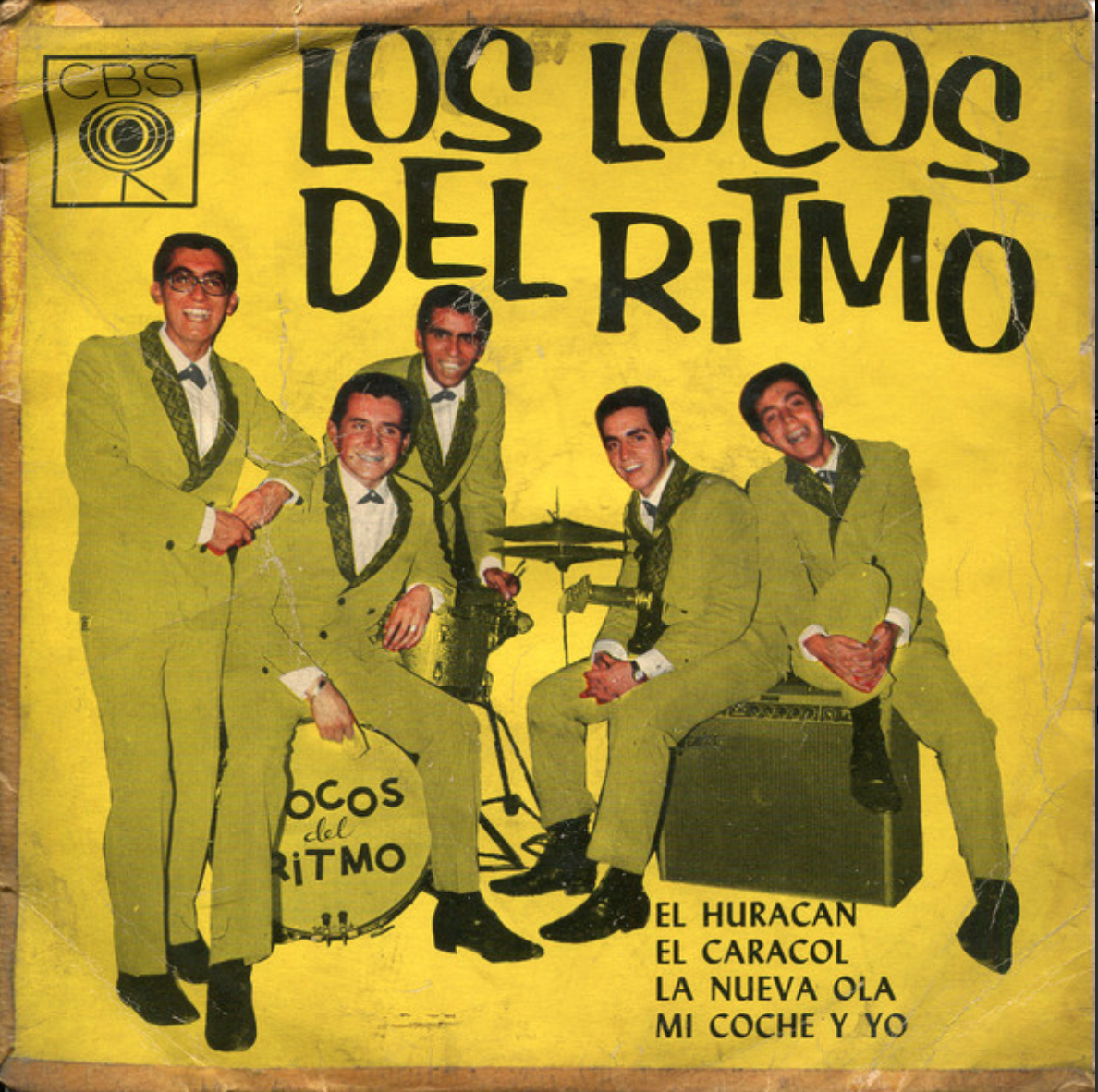

My dad, Lalo Toral, was a rock-and-roll-obsessed pianist through and through. He played with legendary Mexican bands like Los Locos del Ritmo (think: The Beatles in Spanish) who helped pioneer rock music in Latin America, and appeared in the 2007 documentary Rock n Roll Made in Mexico: From Evolution to Revolution. Later in life, he toured the world with El Trí — the “Rolling Stones of Mexico.” He lived hard and loved hard, and his music carried farther than anything else ever could.

In 2011, for Día de Muertos, I visited the Toral family in Mexico City, and it moved me deeply. Every home had an ofrenda. Beautifully decorated with photos of lost loved ones, pets, ancestors. As stories and laughter filled each room, I felt like I was meeting family I’d never known. It was strangely celebratory. Mexicans don’t welcome death as a friend, but they respect it as part of life. Even the tales of José de León Toral, my great-great-uncle who assassinated the Mexican president in 1928, were told with a mix of awe, humor, and family pride.

My cousin Ernie (the fella with his hands behind his back in the photo next to the white VW Bug, and in overalls when we were little) passed away years ago from a congenital liver condition. We only shared those moments together as kids, but he left a lasting impression. His photo has a permanent place on my Día de Muertos ofrenda.

I LOST MY DAD THIS YEAR

Lalo Toral died March 2025. That dang ol’ rock-and-roll-obsessed pianist kicked the bucket. He chased music like it was oxygen. His talent and fire left their mark on stages and souls across Mexico, and the country mourned for him. As a father, his love didn’t always reach as far as his music did, but he seemed to have a fierce desire to show his care for me when he had the chance. Losing him has been a strange kind of heartbreak. Part grief, part gratitude. For the beautiful, complicated man who taught me…close to nothing…but also so much.

HERE IS TAMI AS A CLEANSER

ABOUT AT CdM

I want to dig into my distant history as a chilanga, born of a Mexicano and a gringa, plus have a good time with you: enter a dinner party about muerte!

Let’s slip into the traditions of a Mexican household. I’m going to make traditional Mexican recipes of mole (the hard way), salsas, tamales and cócteles.

You bring with you a memento or photo of a lost loved one, pet, or admired figure. For example, when I experienced Día de Muertos in Mexico City, it wasn’t too long after Michael Jackson had died, and it seemed like the whole country was selling tiny clay MJs. Similarly, they had tiny, big-boobed, Anna Nicole Smiths

We’ll paint our faces. I’ll have a full spectrum of high-quality face paint, jewels, brushes and flowers and I will happily help skull you up. You can do as much or as little as you feel comfortable.

After dinner, we’ll gather around the ofrenda and tell anecdotes of our lost pals. You never know…at midnight we just might see them again.

Feel free to bring drinks to share, if you’d like. It’s a convivial household, after all.

I MISS YOU (NOT IN A DED WAY)

Angel Teta: You’ve been at every Día de Muertos (DdM) at CdM, sprinkling love, whiskey-chaos, and kitchen wizardry like confetti. I miss you daily! Your energy, your laughter, your knack for turning every moment into a memory. You’re out there conquering the world like the hustling boss babe you’ve always been, and somehow, that makes me miss you even more. Kentucky, damn your mash-bills and centipedes!!

Erick Russ: You are a riddle wrapped in a hoodie. Outwardly a bro-y hustler, inwardly a soft, mushy hearted dood who loves fiercely. Every dinner and gathering at my table and in the city give me a moment to think of you once being there! (Except the new restaurant openings I don’t get to invite you o) The 2025 ofrenda will have the photos of the loved ones you once shared, a gentle reminder that even chaos you once had with them still lives on. New York, damn you with your other Angel and your seemingly epic bike paths. #eyeroll #thisisntthesims

Angel Tucker: you never came to DdM at CdM (probably because we were serving spaghetti and meatballs). But I miss the eff bomb dot com out of you nevertheless. Every day I miss you. You SATAN making, marathon-running, sweat-loving, banking VP bombshell.